In their book, Teaching as a Subversive Activity, Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner call for teachers not to be bound by “the syllabi and curricula and textbooks in the schools,” nor by “standardized tests.” Nor should teachers be limited by any “curriculum mandate” (59). Instead, they say, teachers must be in pursuit of relevance. Teachers must discover what is relevant to their students, and to themselves, for, Postman and Weingartner assert, teachers cannot hope to “help a learner to be disciplined, active, and thoroughly engaged unless he perceives a problem to be a problem or what is to-be-learned as worth learning, and unless he plays an active role in determining the process of solution” (52). The objective of teaching that is a subversive activity, they assert, is “to extend the child’s perception of what is relevant and what is not,” for, they continue, “unless an inquiry is perceived as relevant by the learner, no significant learning will take place” (81). “No one will learn anything he doesn’t want to know,” Postman and Weingartner say (52).

Teaching as a Subversive Activity was one of the first books I read as I began to develop as a teacher, and many things Postman and Weingartner said have had a profound and lasting effect on my teaching, over the years. I was reminded of their book again when I read Teaching Shakespeare, recently, by Rex Gibson, creator and editor of the Cambridge School Shakespeare series. Gibson says, in a statement that sounds very similar to what Postman and Weingartner have declared:

Successful Shakespeare teaching is learner-centered. It acknowledges that every student seeks to create his or her own meanings, rather than passively soak up information. The Shakespeare teacher’s task is to enable students to develop a genuine sense of ownership of the play. That entails active expression: helping students to ask their own questions, to create and justify their own meanings, rather than having to accept only the questions and interpretations of others. (9)

In response to the question, “Why teach Shakespeare?” Gibson replies, “Why not?” and then goes on to list examples of students’ “intense engagement” with the plays teachers have reported to him (1).

Interestingly, in her book, Creative Shakespeare: The Globe Education Guide to Practical Shakespeare, Fiona Banks, Head of Learning for Globe Education at Shakespeare’s Globe, asks the same question, “Why do we teach Shakespeare in school?” and notes that a “simple answer” is “because it’s on the curriculum.” But, she insists, such a response is “inadequate.” Teachers must, she says, find their “own reasons to teach Shakespeare that go beyond the demands of curricular fulfillment” (10). Banks stresses “the value that each teacher as an individual brings to their teaching of Shakespeare” (2).

It is just those reasons—that value—brought to the teaching of Shakespeare by individual teachers that I want to examine, as this discussion continues. “What is the necessary business of schools?” Postman and Weingartner ask (15). The answer in their book is to provide students “with a ‘what is it good for?’ perspective . . .” (13). But “most teachers,” they contend, “have the idea that they are in some other sort of business” (13) and, thus, are responsible for “inflecting upon children the kinds of irrelevant curricula that comprise most of conventional schooling” (41).

Postman and Weingartner are especially interested in the reason offered by teachers and others commonly referred to, they say, as “humanist.” Humanists make the argument that a certain subject is “good in itself,” that the subject is “inherently good,” and that it has “intrinsic merit,” or a certain subject is “good for its own sake.” These teachers believe, Postman and Weingartner explain, that such a subject should be taught because it “will do something for their students . . .” (42).

It is common for these teachers to believe, Postman and Weingartner say, “that they are in the ‘information dissemination’ business . . . or in the ‘transmission of our cultural heritage’ business” (13). What they are identifying here is something like the “canonical knowledge” movement that began in the 1980’s, with E. D. Hirsch’s book Cultural Literacy. It is not difficult to recognize Hirsch’s objective, as it is stated in the book’s subtitle, “What Every American Needs to Know,” in this statement about what humanists “believe,” from Postman and Winegartner:

There are thousands of teachers who believe that there are certain subjects that are “inherently good,” that are “good in themselves,” that are “good for their own sake.” When you ask “Good for whom?” or “Good for what purpose?” you will be dismissed as being “merely practical” and told that what they are talking about is literature qua literature, grammar qua grammar, and mathematics per se. (42)

Such “business,” Postman and Weingartner say, which, “in plain truth . . . passes for curriculum in today’s schools, is little else but a strategy of distraction” (47). And here they explain more fully why such business is not relevant:

It is largely designed to keep students from knowing themselves and their environment in any realistic sense; which is to say, it does not allow inquiry into most of the critical problems that comprise the content of the world outside the school. (47)

Earlier, Postman and Weingarten have argued:

It is . . . insane for a teacher to “teach” something unless his students require it for some identifiable and important purpose, which is to say, for some purpose that is related to the life of the learner. The survival of the learner’s skill and interest in learning is at stake. (42)

Reasons for maintaining that the teaching of Shakespeare in school is inherently good, or is good for its own sake, are not difficult to find, and, indeed, abound. For example, Rex Gibson, in Teaching Shakespeare argues that “Shakespeare’s characters, stories and themes have been, and still are, a source of meaning and significance for every generation,” and Gibson adds that while readers of all ages can “recognize and identify” with the “individual emotions” of Shakespeare’s characters, and the relationships Shakespeare brings to life, the plays “also explore issues which beset every society . . .” (2). The plays, Gibson concludes, deal with “abiding questions of how people should live together, of justice, politics, wealth, war” (3).

Cicely Berry also provides a rationale for the inherent value in the words of Shakespeare and the teaching of Shakespeare in school. Berry, who was voice director for many years at the Royal Shakespeare Company, in an interview with Dan Poole and Giles Terera, in Muse of Fire, calls Shakespeare “this unbelievable genius—unbelievable genius.”

In his interview with Poole and Terera, the actor Tom Hiddleston calls Shakespeare “the most intelligent, the most compassionate, the most psychologically forensic, the most emotionally truthful writer that has ever lived.” And Hiddleston continues that Shakespeare’s “depiction of the whole of human life is so rich and so deep and so detailed and has universal access to every soul of every age that he speaks to us and his writing shows us who we are.” Hiddleston goes on to call Shakespeare “one of the greatest artists who ever lived,” and says that this is so because Shakespeare “speaks to every man and every woman at every age in every time.”

Possibly, Fiona Banks makes the most compelling, vivid case for the value of Shakespeare as, she says, “a cultural icon.” The plays and Shakespeare himself, Banks tells us in Creative Shakespeare, “take a central role in most mainstream perspectives of high art . . .” (11). Shakespeare’s plays, Banks continues, “are full of amazing, stimulating and challenging stories that captivate the imagination.” The plays, she says, “contain stories worth ‘hearing.’” They are “universal stories,” and she goes on to explain:

The characters that people them are complex and diverse. Their dilemmas are of their time but simultaneously modern. The stories are timeless and enable students to gain perspective, a sense of themselves and of the universality of the human condition. (10)

This position, which recognizes the “universality” of Shakespeare’s words, his poetry and plays—what Hiddleston calls his ability to speak “to every man and every woman at every age in every time,” and, in Rex Gibson’s words, the “meaning and significance” he holds “for every generation” (2)—allows educators to make the argument that the subject of Shakespeare should be “prescribed” to students, to use the language of Postman and Weingartner, “under the supposition that the ‘subject’ will do something for them”—that it will be “good” for them (42). Ken Ludwig provides another example in his book, How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare: “Shakespeare isn’t just one of the many great authors in the English language. . . .Shakespeare’s powers as a writer simply exceed those of every other writer in the history of the English language” (7). Fiona Banks adds that “If we do not introduce young people to Shakespeare’s plays we deny them some of the tools they need to decode and critique the world around them.” In fact, she states, “we deny them cultural capital” (11). Ludwig is more practical in his remarks to students, even as he makes a similar argument: “To know some Shakespeare gives you a head start in life” (7).

But while recognizing Shakespeare’s universality provides a rational for introducing his plays and poetry to students, for teaching his work in schools, such a position, what Rex Gibson calls “Shakespeare as icon”—recognizing Shakespeare as a “national and international icon: the Great National Poet, who speaks universal truths” (42), such a position, what Gibson goes on to label “bardolatry,” must be avoided. Gibson warns darkly that “students often react unfavourably to being told that Shakespeare is the greatest” (154).

In a conversation in Muse of Fire with Dan Poole and Giles Terera, Patrick Spottiswoode says that such an attitude about Shakespeare and his plays and poems comes from a “reverence” for Shakespeare. “And I think, you know, we do tend to go to the theatre with this kind of reverential attitude for Shakespeare,” he says. “With Shakespeare,” Spottiswoode explains, “there’s this kind of revering.” When Shakespeare’s plays are approached with this “reverential attitude,” Spottiswoode explains in Muse of Fire, students often retreat with “Shakefear,” suffering from an aversion to Shakespeare—for, he declares, “as soon as you’re asked to revere someone, you hate him. You don’t want to know.”

Students are often asked by teachers to approach Shakespeare with this reverential attitude. Teachers who do so, in a term furnished by Postman and Weingartner, treat Shakespeare as a “subject,” which, they say, “leaves out the learner, which is really another way of saying they leave out reality” (42). To teach Shakespeare in this way, they continue, allows classroom teachers to make the argument that the subject of Shakespeare should be “prescribed” to students, to use the language of Postman and Weingartner, “under the supposition that the ‘subject’ will do something for them”—that it will be “good” for them (42). Postman and Weingartner forcefully argue against such an approach in Teaching as a Subversive Activity; they are, “after all, trying to suggest strategies for survival as they may be developed in schools.” And they continue, “we believe that the schools must serve as the principal medium for developing in youth the attitudes and skills of social, political, and cultural criticism.” And so, they say, such a “situation requires emphatic responses” (2).

A central tenant of Teaching as a Subversive Activity is that “the critical content of any learning experience is the method or process through which the learning occurs” (18). This is in opposition, Postman and Weingartner say, to the “notion” that “a classroom lesson is largely made up of two components: content and method.” Educational discourse, they continue, holds that this separation of content and method is “real, useful, and urgent,” and “ought to be maintained in the schools” (18).

The problem is, Postman and Weingartner explain, when content and method are separated (a notion around which “all schools of education and teacher-training institutions are organized”) method becomes trivial, while content is “always thought to be the ‘substance’ of the lesson” (18). In opposition to this, Postman and Weingartner argue:

In order to understand what kinds of behaviors classrooms promote, one must become accustomed to observing what, in fact, students actually do in them. What students do in the classroom is what they learn. (19)

This idea Postman and Weingartner attribute to the educationalist, John Dewey, who, they say, “stressed that the role an individual is assigned in an environment—what he is permitted to do—is what the individual learns.” Dewey believed, they continue, “we learn what we do” (18).

It is clear that students sitting passively in a classroom, a textbook copy of one of Shakespeare’s plays in hand, reading without understanding or interest, are not experiencing what it is audiences recognize and value most highly at the performance of a Shakespeare play. It is clear that such students are not experiencing the “power of Shakespeare’s wisdom,” or the “clarity of his insights into the human condition” that Tom Hiddleston reports about a production of Much Ado About Nothing that hit him with “force,” and “gripped and riveted” him to his seat. The actors in that production, Hiddleston says, take Shakespeare’s “writing off the pedestal of high art and high-spoken inaccessible poetic dramatic language and make it real.” Shakespeare’s words in that production, Hiddleston continues, “just completely relate to the people.”

The production that Hiddleston describes to Dan Poole and Giles Terera—the 1993 film, directed by Kenneth Branagh—does not rely on an audience’s “reverential attitude” toward Shakespeare, but, instead, makes Shakespeare’s writing “real.” Instead of placing Shakespeare’s words on “the pedestal of high art and high-spoken inaccessible poetic language,” Branagh’s production lets Shakespeare’s words “just completely relate to the people.” Branagh’s approach in the film, according to Postman and Weingartner, is subversive; such an approach, says Gibson, is “learner-centered” (9).

Patrick Spottiswoode has noted that, for “young people . . . there’s no reverence for Shakespeare at all”; so, he continues, for actors in a production of a Shakespeare play, “they’re not banking on reverence. They’ve got to earn it. They’ve got to be in the ‘now’ all the time.” And teachers with a classroom of students studying a Shakespeare play, Spottiswoode says, often find themselves in a similar situation. If such teachers “lead a class without actually engaging visually—viscerally—with the audience—with their students—well, they’re going to be pelted.” As with an audience in the theater, for young people in a school classroom, Spottiswoode concludes, “it’s gotta be visceral.”

In her essay, “Learning with the Globe,” which is included in Shakespeare’s Globe: A Theatrical Experiment, Fiona Banks calls attention, as well, to the “synergy” that exists between actors and teachers; she explains:

Both know the challenge of engaging an audience in an environment that is unpredictable and potentially distracting. Equally, both can experience the joy of theatre and learning that is collaborative.” (159)

While it is true, Banks says, in Creative Shakespeare, when we “simply” read a play by Shakespeare, “we get the story, we read the words,” but, she says, we miss its “richness and depth” (4). We must, she says, avoid “reading his plays without any form of active engagement, without his words in our mouths and emotions and actions in our bodies” (3). Banks goes on to say this about the actors for which Shakespeare wrote the plays:

They explored the play by playing: by acting it for an audience, by speaking the words,by experiencing their characters’ emotions, actions, reactions and their relationships with those around them. (4)

The “play’s first readers,” that is, “its actors,” were engaged in “a process of composition and production,” Simon Palfrey says in his book, Doing Shakespeare, “that perfectly harnesses the dense and playful word-use of Shakespeare” (5). For his “company of players,” Palfrey continues, “doing Shakespeare” meant “the reading, exploring, and performing of his parts.” Palfrey goes on to explain that “the experience of the play, for those enacting it, is therefore in the moment, unfinished.” It is, Palfrey says, a process that involves “surprise,” and “adoptive improvisation” (6).

Rex Gibson, in Teaching Shakespeare, makes a similar suggestion, explaining that “Shakespeare wrote his plays for performance, and his scripts are completed by enactment of some kind.” Classroom practices should help students “make Shakespeare their own, as they inhabit the imaginative worlds of the plays through action” (xii).

In a conversation with Dan Poole and Giles Terera in Muse of Fire, the director Michael Fentiman recognizes the importance of speaking and acting out the plays on a stage, as opposed to reading them. Fentiman recalls his earliest experiences with Shakespeare, which, he says, “probably divide into two, really,” Fentiman recalls. One of those experiences was reading The Merchant of Venice in English class, and he remembers “finding it a bit—a bit rubbish.” It could have been, he briefly considers, that it was taught badly, but, he says, again, “I found it boring . . . . just boring.” Sometime later, he says, “I snuck into the interval of a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, at my local theatre. . . .and I was really laughing. I thought it was funny.” Fentiman goes on to explain:

You know, there were bits I didn’t understand, but I didn’t really mind. I found it fascinating. The bits I didn’t understand I found fascinating. The bits I did understand I found funny—or kind of engaging.

And here he sums up these experiences:

So in a way I had two experiences of Shakespeare. One was the literary one; one is sitting down and reading it and in doing that finding it really, really boring. And then one is about going to watch it and experiencing it viscerally and then loving it. So I divide the two things in my head. I had two—I had two first experiences. The live one—one where I was there watching—it was far more—joyful.

Rex Gibson describes what behaviors, for him, allow students to learn in a Shakespeare classroom, and those behaviors nicely parallel the experiences Michael Fentiman describes to Poole and Terrera:

Shakespeare was essentially a man of the theatre who intended his words to be spoken and acted out on stage. It is in this context of dramatic realization that the plays are most appropriately understood and experienced. (xii)

These comments parallel John Dewey’s emphasis on what students do in the classroom, as well. “It really is as simple as that,” conclude Postman and Weingartner, in Teaching as a Subversive Activity: “If you don’t do it, you don’t learn it” (24).

Fiona Banks is more specific in her description of what behaviors allow students to learn in a Shakespeare classroom. “I’m interested in the journey from the rehearsal room to the classroom,” she says. Banks is interested, she says, in “how a technique used to create performance can equally become a catalyst for learning” (xv). In Teaching Shakespeare, Rex Gibson draws a parallel similar to the one drawn by Banks:

The co-operation that exists in such classrooms, as students work together on “their” Shakespeare, mirrors the creative, experimental ethos of the theatrical rehearsal room, where individual talents unite in co-operative enterprise. (1)

Gibson describes the “intense engagement” of students studying Shakespeare in such a school classroom, one in which there is “a wide range of expressive, creative and physical activities.” And he concludes, “The consequence for teaching is clear: treat the plays as plays, for imaginative enactment in all kinds of different ways” (xii).

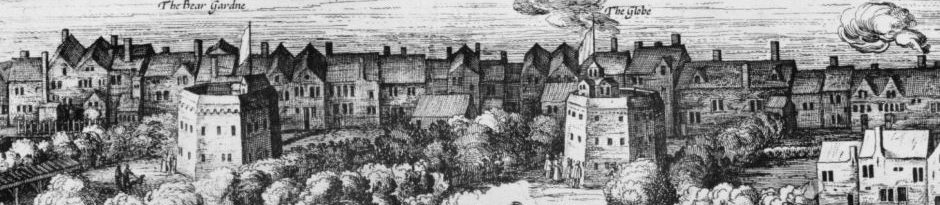

Simon Palfrey begins a useful discussion in Doing Shakespeare that perhaps describes such a “creative, experimental ethos.” Palfrey notes that “Shakespeare was very popular in his day, and he has remained very popular pretty much ever since.” Even so, Palfrey continues, “Shakespeare is not easy,” and “has probably never been easy.” Shakespeare’s fellow actors at the Globe knew that it took effort to understand him. Their instruction in the 1623 collected plays, the First Folio, directs readers, Palfrey says, to “look harder; do not expect what you usually expect; search for what lies hidden.” If such instruction, Palfrey continues, “was necessary then, it is no less now” (1). Here is what Palfrey says modern readers must learn that the actors at the Globe must surely have known:

. . . it is only by acknowledging Shakespeare’s difficulty and unpredictability—dwelling within it, grappling with it—that we can begin to recover the particular energies of his plays. (7)

Giles Terera asks Tom Hiddleston in his interview in Muse of Fire, “What is it you want to have achieved” with a Shakespeare performance? “What is it you want to do—” Terera asks, “to do with these plays?” When approaching a text by Shakespeare, Tom Hiddleston explains, “what I want to do . . . is to remind audiences of the breadth of his wisdom, and to package it in such a way that that’s accessible to people—that it doesn’t seem to be somehow at a distant reach.” Hiddleston continues:

I suppose—I suppose what I’m saying is—is—the learning is so important—the—the personal, intellectual, emotional navigation of his eloquence and articulacy is so crucial if you’re going to take people on a journey with you—on an emotional journey.

Such an approach to a play is what is realized through “the cooperation that exists” in “the creative, experimental ethos of the theatrical rehearsal room,” as Rex Gibson describes that space in Teaching Shakespeare, and which Gibson goes on to describe as a space “where individual talents unite in cooperative enterprise.” In that approach to Shakespeare’s texts, teachers and their students, in turn, can strive to mirror such a “creative, experimental ethos” (9).

In Creative Shakespeare, Fiona Banks says that, for actors, “rehearsals are not about right answers but asking questions and exploring possibility.” Banks notes that, for actors, the “rehearsal process,” often includes these activities:

Exploring the text actively, discovering aspects of the play by “playing.” Playing their character but also being playful and experimental in their approach. Being inspired by the language of the plays, trying different ideas until they find the right one for their particular interpretation. (4)

Tom Hiddleston makes a similar case for the ascendency of the rehearsal room ethos. “The worst place for Shakespeare in a way,” he says, “is the schoolroom”:

Shakespeare should never seem like work. I mean—it is hard work, but it is rewarding work. But it should never be—it should never be wrapped up as something that’s hard or difficult to understand. Because once you unlock it—if you just find a way to unlock it—suddenly it all makes sense to you.

“All it needs,” Hiddleston repeats, “is just unlocking.” It is necessary, he insists, to find “whatever turns the light on for you.” He continues, in his conversation with Poole and Terera, describing “Shakespeare’s difficulty and unpredictability” noted by Simon Palfrey:

Shakespeare’s poetry is like a labyrinth and its—his verse is so full of twists and turns which at first can seem confusing and befuddling and intimidating. But if in preparation on your own you’ve worked out a route from the outside to the center and you know that you have to take this turn and then this turn and then go ’round the back of this and then come in this way.

The goal of the actor is to lead the theatre audience through the play, to thrill, to move, to inspire them, as they journey through the labyrinth. The actor who is prepared, Hiddleston continues, who knows his way through the labyrinth, “can lead other people faster and with clarity and fun.” To make them trust you as a leader, Hiddleston says to the actor, to insure that they’ll “come with you,” experience the play with you—“go on the ride,” he says—the actor must be prepared to let the audience in on “every emotional high, every emotional low, every pearl of wisdom, every fantastic joke, every humanistic revelation.”

The goal for the actor, Hiddleston says, is an absolute understanding of the play—an understanding that allows the actor to grasp its meaning, himself, and, at the same time, to communicate that meaning to the audience. “The work you have to do is really in the preparation of understanding it,” Hiddleston says, “really, really, deeply understanding it.”

Teachers, I am suggesting here, can journey with students experiencing Shakespeare in school in ways similar to how Hiddleston says actors journey with audiences in the theatre. The teacher as well as the actor must tend to Shakespeare’s “eloquence and articulacy,” but also to “package” Shakespeare’s wisdom so that it is “accessible to people.” Teachers, as well as actors, must know, Hiddleston says, the “breadth” of Shakespeare’s “wisdom,” and each must have packaged “it in such a way that’s accessible to people—” in such a way “that it doesn’t seem to be somehow at a distant reach.”

Giles Terera’s question to Hiddleston, “What do you want to do with the plays?” is a question for teachers to answer, as well. In both rehearsal space and classroom space, the actor, as well as the teacher, has many choices to make. To guide us in making such choices, again, we must look to the “theatrical rehearsal room” to that space described by Rex Gibson, where, he says, creativity and experimentation thrive.

In her interview with Dan Poole and Giles Terera, in Muse of Fire, actor, Geraldine James seems to be referring to this function of the teacher in a similar way. She says that her wish is that in teaching Shakespeare, “teachers would just teach it differently.” What she’d really “sort of wish,” she says, is “that they’d let actors go into schools and talk about” the plays.

The role of “navigator” for the teacher is also discussed by the director, Sean Holmes, who talks, as well, to Poole and Terera in Muse of Fire. Holmes speaks first of “the sense of excitement and wonder” he remembers in studying the plays, and the “possibility and range and depth” of Shakespeare’s poetry, then he describes his experience with “three or four very good English teachers in school.” Holmes and the other students in his class “did King Lear and Othello and we all got really into Othello, and he did. . . .and we all got really into the play’s language. . . .He was a really good teacher.” Holmes’ words reveal how important his teacher’s involvement and deep understanding were for Holmes’ positive experience. “And I can really remember,” Holmes says, “this sense of excitement and connection with the language.”

What teaching Shakespeare as a subversive activity requires, Postman and Weingartner say, is expressed well by I. A. Richards, in Interpretation in Teaching, who argues for a way of studying language “as the major factor in producing our perceptions, our judgments, our knowledge, and our institutions.” Here, Postman and Weingartner quote Richards:

. . . a deeper and more thorough study of our use of words is at every point a study of our way of living. It touches all the modes of interpretative activity—in techniques, and in social intercourse—upon which civilization depends. (103)

For the study of language to be “meaningful,” it must be “the study of our ways of living” (104). They emphasize that “the study of language is the study of our ways of perceiving reality,” for, they say, “the study of language is inseparable from the study of human situations” (54). So, they conclude, “a language situation (i.e., a human situation) is any human event in which language is used to share meanings.” Such situations, Postman and Weingartner tell us, are “real, may easily be encountered,” and are “therefore useful to know about” (55).

For actors such as Hiddleston and James, the quest for clarity and engagement in their exploration of Shakespeare’s poetry and the level of their immersion in the task indicate their regard for the language of the plays as a regard for, in I. A. Richards’ words, “our way of living.” Their concern with the language of the plays indicates their concern with the “modes of interpretive activity . . . upon which civilization depends.” Shakespeare’s poetry, as a result, becomes, for students led through a text full of “twists and turns,” a text “inseparable from the study of human situations.” This is the regard for language and engagement with a text by Shakespeare that Hiddleston and the other actors allude to throughout this discussion. This is what Rex Gibson alludes to when he insists that only “in the context of dramatic realization” can the plays be “most appropriately understood and experienced” (xii). Banks says, in Creative Shakespeare, that by “engaging actively with text, students gain ownership” of the play they are studying and they can “make it relevant to themselves, and in doing so play a part in reinventing Shakespeare for the current age, making the plays worth studying” (6).

When teaching Shakespeare is a subversive activity, his work is understood as relevant to students. This means, Simon Palfrey says in Doing Shakespeare, “that the plays have to speak with immediacy and urgency” (8). In a phrase provided by Postman and Weingartner, it means the plays must serve “some purpose that is related to the life of the learner” (42).

References

Banks, F. (2013). Creative Shakespeare: The Globe Education Guide to Practical Shakespeare. New York: Bloomsbury.

Banks, F. (2015). “Learning with the Globe.” In C. Carson & F. Karim-Cooper (Eds.)Shakespeare’s Globe: A Theatrical Experiment (pp. 155-165). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Berry, C. (n.d.). Interviewed conducted by D. Poole and G. Terera. Muse of Fire. Retrieved January 5, 2018 from https://globeplayer.tv/museoffire.

Carrol, T. (2015). “Practising Behaviour to His Own Shadow.” In C. Carson & F. Karim-Cooper (Eds.) Shakespeare’s Globe: A Theatrical Experiment (pp. 37-44). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fentiman, M. (March 8, 2014). Interview conducted by D. Poole and G. Terera. Muse of Fire. Retrieved January 12, 2018 from https://globeplayer.tv/museoffire.

Gibson, R. (1998). Teaching Shakespeare. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hiddleston, T. (January 11, 2013). Interview conducted by D. Poole and G. Terera. Muse ofFire. Retrieved January 12, 2018 from https://globeplayer.tv/museoffire.

Hirsch, E. D. (1987). Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Holmes, S. (May 14, 2015). Interview conducted by D. Poole and G. Terera. Muse of Fire. Retrieved January 5, 2018 from https://globeplayer.tv/museoffire.

James, G. (August 26, 2009). Interview conducted by D. Poole and G. Terera. Muse of Fire. Retrieved January 14, 2018 from https://globeplayer.tv/museoffire.

Ludwig, K. (2013). How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare. New York: Broadway.

Palfrey, S. (2011). Doing Shakespeare. London: Bloomsbury.

Postman, N. & Weingartner, C. (1969). Teaching as a Subversive Activity. New York: Dell.

Richards, I. A. (1949). Interpretation in Teaching. London: Routledge.

Spottiswoode, P. (n.d.). Interview conducted by D. Poole & G. Terera. Muse of Fire. Retrieved February 18, 2018, from https://globeplayer.tv/museoffire.